Michigan at a Crossroads

Schools can lead the way to a zero-waste future

Pairing Better Landfill Emissions Rules with Organics Diversion Delivers Michigan’s Biggest Climate and Health Win

Every year, hundreds of thousands of tons of organic waste — food scraps, food-soiled paper, cardboard, and wood — are buried in Michigan’s landfills. Once underground, without oxygen, this material decomposes and releases methane, a greenhouse gas that traps more than 80 times as much heat as carbon dioxide in the short term.

Methane from landfills is one of Michigan’s most preventable sources of climate pollution, and one of its biggest opportunities for near-term action. But landfill emissions don’t just warm the planet. They also harm people and communities. Alongside methane, landfills spew contaminants like heavy metals, hydrogen sulfide, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that poison the air and water in nearby communities, worsening or leading to conditions like asthma, coronary heart disease, and cancer.

For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency found that violations at the Brent Run Landfillin Genesee County caused excess emissions of hydrogen sulfide, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and volatile hazardous air pollutants (VHAPs) — pollutants that contribute to respiratory distress, nausea, and long-term health risks. Unfortunately, Brent Run isn’t an outlier. Michigan has 60 reported municipal solid-waste landfills, and one in four Michiganders lives within five miles of one — the same population as nearly four Detroits.

Michigan’s Landfill Methane Problem — and Its Fix

Michigan has one of the highest per-capita waste burdens in the U.S., in part because its landfills make money off of accepting large volumes of trash shipped in from other states and from Canada. That waste generates millions of tons of methane and other pollutants each year.. Our analysis, detailed in Michigan at a Crossroads: Break Free From Status Quo Waste Policies, shows that stronger landfill standards — earlier gas collection, improved cover systems, and proactive leak detection — could cut landfill methane emissions by about 57 percent by 2100.

But better rules alone can’t solve the problem. To make deep, durable reductions, Michigan must also keep organic waste out of landfills. When strong methane rules are combined with statewide waste diversion — recycling, composting, and food donation — emissions fall even further:

If Michigan strengthens landfill rules, meets existing organic diversion targets, and increases the overall recycling rate to 45 percent by 2050, we can achieve a 64 percent landfill methane reduction by 2100

If Michigan does all of the above and implements expanded organics diversion to include paper, cardboard, and wood, we can achieve a 68 percent landfill methane reduction by 2100

If Michigan were to recycle paper and cardboard waste by just five percent more than the status quo,, this would result in 3.5 million additional metric tons of methane avoided between 2025 and 2100 — the equivalent of taking nearly 22 million cars off the road for an entire year.

The combination of better methane controls at existing landfills and organics diversion delivers one of the single most impactful climate, health, and economic wins for the Great Lakes State.

Other states — including Colorado, Maryland, Washington, and California — have already acted with stronger safeguards. Michigan risks falling behind if it doesn’t close loopholes and update outdated requirements. The good news is that there’s a built-in chance to do so: Public Act 235, signed in late 2023, directs EGLE to develop best practices for landfill methane collection and control. That guidance is the key opportunity to fix weak standards and bring Michigan in line with proven approaches elsewhere.

We modeled what happens if Michigan strengthens its rules on top of the progress already made. The results show that EGLE could cut landfill methane emissions by nearly half within 25 years — realizing one of the state’s biggest opportunities to hit the brakes on near‑term climate change, protect communities from harmful air and water pollution, and strengthen local economies.

Jobs and Health Benefits Abound

First, organics diversion and recycling can provide the Great Lakes State with a major economic boost, at a time when Michiganders are feeling the strain of inflation and a stagnant job market. EGLE’s 2024 Economic Value and Characterization of MSW in Michigan report found that recovering more recyclable and compostable materials would generate $610–$825 million annually and create 3,300–4,500 jobs.

Building large-scale composting capacity — 800,000 to 1 million tons per year — would avoid $5–$8 billion in health and climate damages, effectively paying for itself many times over.

Rescuing uneaten and edible food from landfills also means more food on peoples’ plates. Food insecurity is a crisis for Michigan families, with one in five children experiencing hunger in 2023. Why should we spend billions of dollars burying food in landfills, when it could be filling our children' s bellies instead?

Organics recycling and composting are also a win for Michigan's approximately 45,000 farms. Food scraps can be used to feed livestock, and finished compost enriches the soil that our local farmers rely on to feed us.

Every ton of waste diverted reduces methane, saves money, and yields nutrient-rich compost that supports Michigan’s farms and landscapes.

Schools: The Key to Making Organics Diversion Work

One wide-open path to scaling up organics diversion runs through the state’s K-12 schools.. As community hubs, schools are uniquely equipped to lead on waste reduction. Each day, Michigan’s schools serve hundreds of thousands of meals, producing consistent, trackable streams of food waste — ideal for piloting composting and food-waste reduction systems.

Why Schools Are Uniquely Positioned

Scale and reach: Michigan has 4,210 public and private schools across 889 districts as of 2021. Every lunch tray offers a teachable moment.

Education and culture: Youth and students are key members of our communities, and drivers of long-term transformative change. What students do and learn in schools branches out to their families and communities now and in the future. Zero-waste lunchrooms teach lifelong food-saving habits and reduce disposal costs.

Among the largest purchasers and employers in every Michigan community, organic diversion programs are smart financial investments for schools, especially when factoring in reduced food costs, avoided landfill fees, and rebates from recycled cardboard. In fact, after an initial investment, schools may be able to operate successful programs with little-to-no out-of-pocket costs.

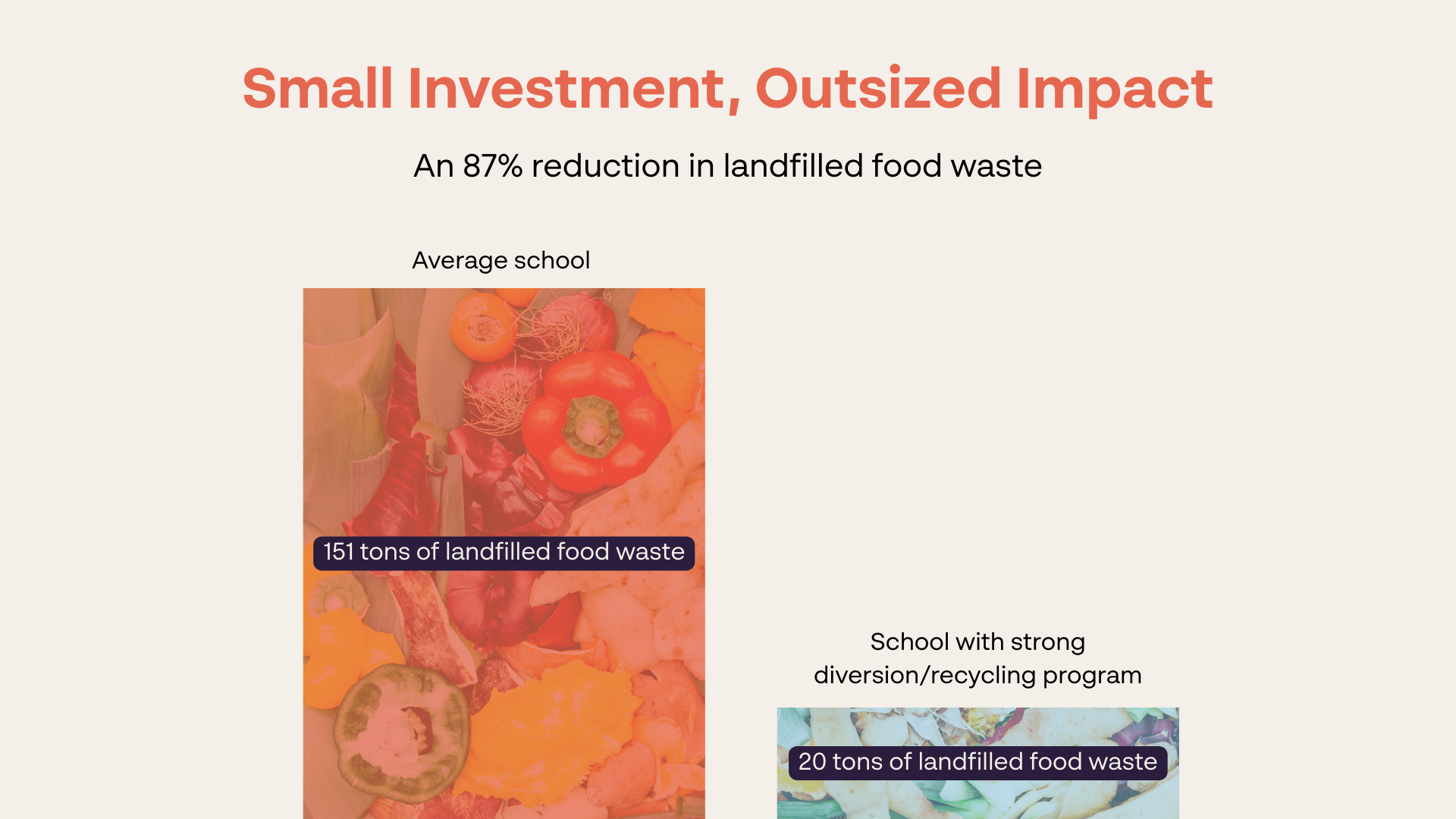

We’ve already seen success stories in action. The Michigan Sustainable Business Forum worked with Michigan’s second-largest school district in 2017 to develop a grant-funded program to increase recycling access: the school with the strongest organics diversion and recycling program sent just 20 tons of waste to the landfill that year, compared to 151 tons for an average-performing school in the district. That is a potential 87 percent reduction in waste sent to the landfill.

If schools can implement programs at scale, the same model can ripple across other institutions — for example, restaurants. According to the Forum, Michigan restaurants with well-managed programs have demonstrated as much as a 1-to-1 reduction in landfill usage when investing in commercial compost service.

Michigan’s Moment to Invest in Proven Track Record of Success

The January 2025 state budget includes $11.8 million in new recycling grants, following $25.6 million invested from 2022–2024. Though there is no dedicated source of funding for composting in schools, directing even a fraction of this funding toward K–12 systems could bring composting and food waste reduction programs within reach for schools across the states.

There are several Michigan schools who are already leading by example. Hayes Elementary demonstrates that zero-waste lunchrooms can work. By separating food scraps for composting and recovering uneaten food, the school significantly reduced the amount of trash it sends to the landfill, while turning lunchtime into a daily lesson. Students lead the effort, staff support it, and the benefits ripple beyond the cafeteria into homes and the broader community. In Ann Arbor and Grand Rapids, student-led zero-waste teams have already cut cafeteria trash in half while educating peers about the importance of reducing food waste. Even more schools are ready to compost and reduce food waste, but need the initial investment to jumpstart success. By allocating funds to food waste reduction programs in K-12 schools, our lawmakers in Lansing have an opportunity to help schools like Boggs jumpstart composting programs and make a tangible difference for their local environment and economy.

The Takeaway

Michigan’s best pathway to durable methane reduction is twofold:

Adopt stronger landfill methane rules to control emissions from existing waste.

Scale up organics diversion — starting with schools — to prevent future emissions.

Together, these actions drive an 11 percent greater overall methane cut than rules alone, preventing more than 3.5 million tons of methane by 2100 and delivering the largest climate, health, and economic benefits available to Michigan’s waste sector.

If we can get it right in our schools, we can get it right everywhere — turning classrooms into catalysts for climate action and communities into models for a zero-waste future.

What teachers and students are saying about school composting programs

"Composting at Hayes has transformed lunchtime into a leadership opportunity for our students. They take ownership of the process, teach one another, and see firsthand how food waste can become a resource instead of trash. At the same time, we’ve reduced what we send to the landfill while empowering students to lead real, meaningful change in their school and carry those habits into their homes and community."

— Christine Lakatos, Hayes Elementary School Teacher and Green Team Leader"At the James and Grace Lee Boggs School, we are committed to being stewards of our environment. It's reflected in our curriculum when students track the waste cycle and make a short film on Youtube. Check out "Trash Life the movie". We practice recycling, work in our school garden, and have solar power infrastructure ready to implement. Composting is our next frontier. It's a part of how we learn and grow together. Launching a successful composting program requires thoughtful planning. It must be rooted in education first and foremost. Dedicated staffing is crucial in sustaining a program and basic composting supplies will help get us started. We recognize that time and money may be barriers to accomplishing our goals. However, we believe by overcoming these hurdles we can start to transform our relationship to food waste."

— Dakarai Carter, Programming Coordinator at The James and Grace Lee Boggs School“My grandpa has a garden in his backyard, and he composts for his garden. I’m in our school’s garden club. It would be good to compost in schools because it can help reduce food waste, it can give students knowledge and a better grasp on agriculture and urban farming, and understand how long it takes different things to break down. Our school has a a garden, and once you start composting, you can use that compost to garden.”

- Amir Al-Din Ware, Senior at Renaissance High School in Detroit, MI