Summary

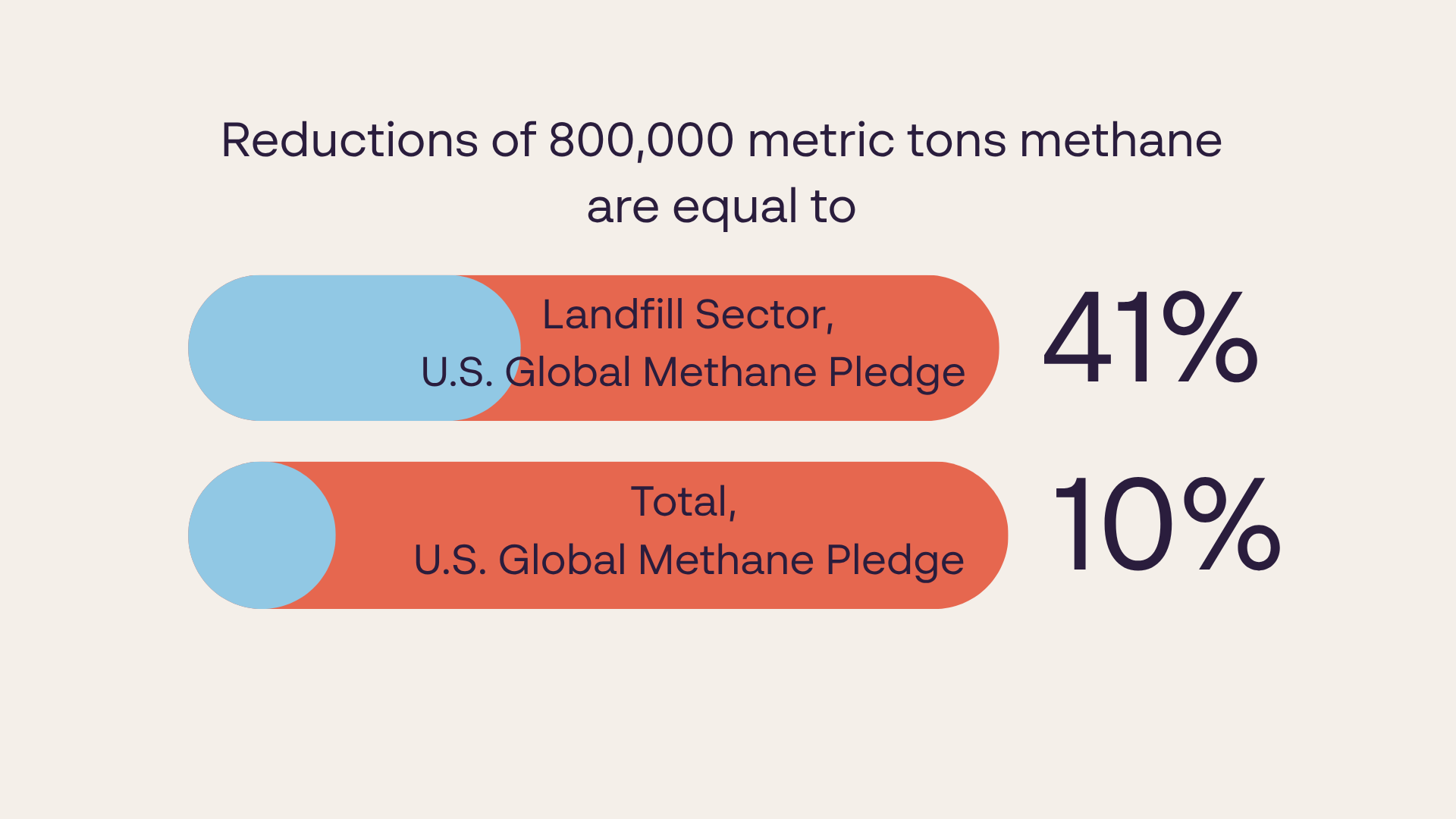

Landfill methane regulations and organics diversion efforts, already underway in several U.S. states and highly achievable in several others, could deliver outsized climate and public health benefits. Together, these subnational actions can cut just over 800,000 metric tons of methane per year, equivalent to 22.4 million metric tons (MMT) CO₂e on a 100-year global warming potential (GWP), representing 41 percent of the U.S. Global Methane Pledge target for the landfill sector and 10 percent of the total U.S. pledge target*. These actions also unlock powerful co-benefits. Controlling methane doesn’t just cut a potent climate pollutant; it also reduces hazardous air pollutants and other harmful gases that threaten air quality, human health, and overall quality of life. Taken together, these benefits provide the immediate, measurable emissions and human harm reductions the U.S. needs as we work to achieve 2030 and 2050 climate commitments.

Introduction

The Global Methane Pledge is an international commitment to cut global methane emissions at least 30 percent by 2030 compared to 2020 levels. For the United States, this translates into a clear, measurable 2030 target that can be met through sector-specific strategies — including tackling landfill methane, one of the nation’s largest sources of this potent greenhouse gas.

Keeping organic waste out of landfills and improving controls on landfill emissions also delivers powerful public benefits: cleaner local air, healthier communities, meaningful environmental justice gains, and job creation in diversion programs. More than half of U.S. landfills are located in communities with elevated rates of chronic illness, disability, or mental distress. Nearly 1,500 landfills are in areas with higher arsenic in drinking water, and about one in three face unsafe levels of ozone or particulate pollution. Many of these same communities also have higher shares of low-income households, young children, or older adults, underscoring the disproportionate health and social burdens tied to landfill siting.

What we Modeled:

Full Circle Future analyzed the emissions reductions that are possible from states that are already acting — or positioned to act — to cut methane significantly, either through tighter requirements to find and capture landfill gas or expanded programs to prevent and divert food scraps and other organic waste. Key policy improvements include:

Organics diversion: Expanding requirements to keep food scraps and other organic waste out of landfills through composting and other beneficial uses.

Lower thresholds for installing gas collection and control systems (GCCS): Many landfills are exempt from following basic operational best practices and installing gas capture systems, as they fall below the federal threshold. States such as Oregon, Maryland, and Washington have implemented lower thresholds for requiring the installation of gas collection systems and stronger operational requirements.

Earlier GCCS installation and expansion: A recent EPA report found that, “Because food waste decays relatively quickly, its emissions often occur before landfill gas collection systems are installed or expanded”. Landfill operators must ensure gas systems are installed and operational as waste is being placed, not after significant amounts of methane have already escaped into the atmosphere.

Comprehensive, effective surface emissions monitoring: Ensure landfills are utilizing 21st-century tools — satellite data, aerial surveys, fixed sensors, drones, and fenceline monitoring — to detect and repair leaks, as demonstrated in California and Pennsylvania.

Improved GCCS design and operation: Standardize robust GCCS design and operational practices, such as integrating horizontal collection systems and linking them with leachate systems, auto-tuning, and other best practices.

Enhanced landfill cover systems: At landfills without active gas collection systems, require optimized soil or biocovers with methane-oxidizing capacity.

These improvements, taken together, significantly increase methane capture and reduce emissions, creating a more uniform and effective regulatory framework. Regulatory solutions must also be paired with organic waste diversion policies to achieve lasting, scalable methane reductions in the long term.

States Modeled:

Already advancing: California (2010 Landfill Methane Rule; 2016 SB1383), Oregon (2021 Landfill Methane Regulations), Washington (2022/2024 Organics and Landfill Regulations), Maryland (2023 Landfill Air Regulation), Colorado (2025 Regulation 31 draft)

Poised for progress: Michigan (SB 271 signed into law, pending implementation), New York (2023 Solid Waste Management Plan proposed), Illinois (HB1707 introduced), and California (2025 Landfill Methane rule update in progress).

Key Findings

If all eight U.S. states implemented more effective state landfill regulations and organic waste prevention and diversion policies, they could collectively:

Reduce methane emissions by just over 800,000 metric tons of methane per year, equivalent to 22.4 MMT CO2e on a 100 year GWP in 2030 or the same as reducing emissions from driving 5.2 million cars for a year.

This equals a 12% reduction in annual U.S. landfill methane emissions compared to 2020 levels, meeting 41% of the Global Methane Pledge target for the United States Landfill Sector and 10% of the total U.S. pledge target.

Why This Matters

Achieving these reductions — through practical, proven, and cost-effective solutions — would take the U.S. nearly halfway to meeting its landfill-sector contribution to the Global Methane Pledge. This analysis underscores the significance of updated and more effective landfill methane emissions standards and the pivotal role that subnational action can play in driving national climate and environmental justice progress.

Despite being unseen and often under the radar, trash and the greenhouse gas emissions it generates represent an enormous opportunity to press an emergency brake on climate change. And we can do more than simply slash emissions. By reimagining our relationship to what we throw away, we can move away from our toxic “take-make-waste” cycle and toward a regenerative circular economy. State policymakers must seize the opportunity to lead.

Methodology for Estimating 2030 State-Level Contributions to the Global Methane Pledge

We utilized our methodology from our Turning Down the Heat (Oct 2024) report (developed when Full Circle Future was a campaign of Industrious Labs), which, utilizing a comprehensive model, provides landfill methane emissions projections for 2024–2050 under Business as Usual conditions and with improved landfill management standards. We extracted the projected U.S. national landfills emissions specifically for the year 2030 and the emissions reductions that would be enabled with improved landfill management standards. We sourced 2023 state-level landfill estimated methane emissions from the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP), which tracks emissions from municipal and industrial waste landfills. We calculated each state's percentage share of total U.S. landfill methane emissions by dividing the state's reported annual emissions by the national total (sum of all states). Key States GMP calcs Each state’s percentage share (based on 2023 data) was applied to the national 2030 projection to estimate its contribution to the U.S. methane emissions in 2030. Projected emission reductions were allocated from the total U.S. landfill emissions methane reduction potential, based on the same state shares, assuming proportional reductions across states in accordance with their relative contributions.

*The 100-year Global Warming Potential (GWP) is used for methane in this case because it aligns with the methodology used by the IPCC and allows for comparability across greenhouse gases over a standardized long-term timeframe (IPCC, 2021). However, the 20-year GWP would better capture methane’s immediate climate impact. Methane is most potent in the first 20 years after its release, and using a 20-year GWP more accurately reflects the urgency of reducing methane emissions. By contrast, the 100-year GWP averages its effects over a century, which can dilute its short-term climate impact and align it more closely with long-lived gases like CO₂.